Introduction

The Province of Ontario is the most populous province in Canada, home to 38.5% of Canada’s national population as of the 2021 census. Located in Central Canada, it is the political, economic, and cultural heart of the country. Its capital, Toronto, is the nation's largest city and financial centre, while Ottawa, the national capital, lies along Ontario’s eastern edge. Ontario is bordered by Quebec to the east and northeast, Manitoba to the west, Hudson Bay and James Bay to the north, and five U.S. states to the south—Minnesota, Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York—mostly along a 2,700 km (1,700 mi) boundary formed by rivers and lakes in the Great Lakes–St. Lawrence drainage system. Though Ontario is the second-largest province by total area after Quebec, the vast majority of its people and arable land are concentrated in the warmer, more developed south, where agriculture and manufacturing dominate. Northern Ontario, in contrast, is colder, heavily forested, and sparsely populated, with mining and forestry serving as the region’s primary industries.But Ontario is more than just a province; it is the crucible of English-speaking Canada.

In 1784, after the American Revolution, Loyalist settlers arrived with intention, bringing with them the legal traditions, religious institutions, and steadfast allegiance to the Crown that had shaped their former world. They sought to uphold a civilisational order rooted in monarchy, Church, and Law, and to establish a society founded on duty, hierarchy, and restraint. From these early Loyalist settlements, beginning at Kingston, a distinct political and cultural tradition emerged. It was neither British nor American. It became the foundation of a new people.

Today, the descendants of these settlers form the core of an ethnocultural identity known as Anglo-Canadian. Numbering over ten million across the country, and more than six million in Ontario, Anglo-Canadians are known for their enduring institutions: constitutional monarchy, common law, Protestant-rooted civic morality, and a national ethos shaped by loyalty and order. This cultural framework shaped Ontario’s development across every sphere of life.

Loyalists built the province’s schools, banks, and legal systems. They established its early industries, including agriculture, forestry, mining, and railroads, and later came to dominate the professional sectors of law, education, public administration, and finance. Their shining city, Toronto the Good, became the centre of Canadian banking and corporate life, while small towns across the province were anchored by courthouses, parish churches, and grain elevators.

Language and schooling played a central role in shaping the Anglo-Canadian character. Ontario’s education system, from common schools to universities, was built to transmit British values, civic order, and the English language. Protestant denominational schools and later public grammar schools taught the children of settlers to read scripture, study British history, and speak in the elite formal register of English Canada. Institutions such as Upper Canada College, Queen’s University, and the University of Toronto became pillars of elite formation, producing the clergy, lawyers, teachers, and administrators who carried the culture forward.

Culturally, Anglo-Canadians preserved a rhythm of domestic and seasonal life rooted in British tradition but adapted to the northern landscape. Autumn fairs, apple bobbing, and harvest suppers marked the calendar in rural communities. Roast beef, butter tarts, mincemeat pies, and tea with milk became the everyday fare of farmhouses and urban kitchens alike. Sunday observance, cenotaph ceremonies, school uniforms, and service clubs reflected a moral seriousness and civic sense inherited from the Loyalist project. It is this tradition that formed the structural spine of its political and cultural development.

Fire & Blood

The American Revolutionary War, fought between 1775 and 1783, is often remembered as a struggle for independence and popular sovereignty.

For the Loyalists, it was something else. The disintegration of lawful society, rebellion against God, and a betrayal of ancestral inheritance.

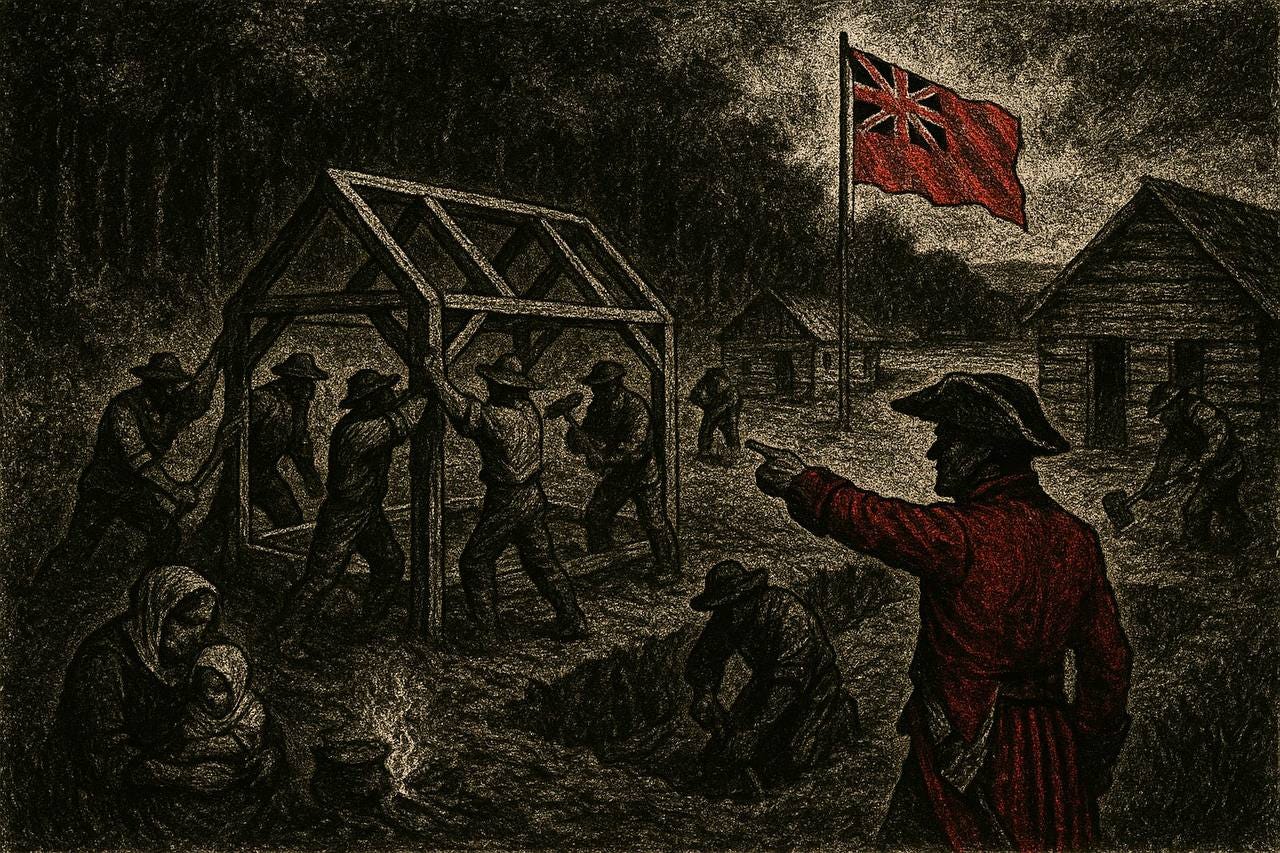

As the fires of revolution engulfed the known world in the 1770s, the Loyalists watched with horror as colonial order collapsed, giving way to the rule of liberal fanatics, sadistic opportunists, and oligarchs. Committees of correspondence, provincial congresses, and armed militias rose up to replace royal governors and lawful magistrates. Clergy were stripped of their pulpits.

Merchants were raided, their goods seized, their homes ransacked by violent mobs. Those who refused to bend the knee to revolutionary madness faced public shaming, exclusion, or raw violence. In New York, Pennsylvania, and the Carolinas, entire families were driven from their land at gunpoint, leading to blood feuds. By war’s end, several state legislatures had passed acts of attainder, naming Loyalists enemies of the republic and seizing everything they owned

The indignation of the Loyalists would deepen into memory. They were hunted as traitors. Their homes were looted, their businesses boycotted, their churches burned. They were tarred, feathered, and dragged through the streets or publicly executed.

Some stayed silent, hoping to endure, such as the Loyalists of the southern states. Others took up arms. In retaliation, thousands enlisted in provincial units raised by the British. The King’s Royal Regiment of New York, the Queen’s Rangers, Butler’s Rangers, the New Jersey Volunteers, and De Lancey’s Brigade. These were not militas, but formal regiments composed of Americans, often better adapted to local terrain and politics than the transplanted British regulars. They conducted raids, defended settlements, and fought in both conventional and irregular engagements.

Their loyalty was tested in knowing they fought against neighbours, even kin, while distrusted by both the revolutionaries who called them traitors and British officers who saw them as auxiliaries. They did not see themselves as failed Americans or transplanted Britons. They believed they were a separate people, imperial in allegiance, colonial in birth, and distinct from both. They believed the revolution would collapse into faction and mob rule. Events in France after 1789 confirmed these fears. In sermons, letters, and essays, Loyalist thinkers returned to the language of duty and providence.

When the war ended with the Treaty of Paris in 1783, Loyalists were unwelcome in the communities they had built. Their property was not restored. Their names remained tainted. Though the treaty promised restitution, its provisions were largely ignored. They departed with a sense of mission. Some went to the Maritimes, others to Britain or the Caribbean. But a large contingent, and their families, turned north to the unsettled forests and rivers of what would become Ontario. Many believed their suffering was divine refinement, a trial by fire to purify the remnant. They saw themselves as the true heirs of English constitutional liberty upholding the ancient tradition of King, Lords, and Commons, and condemned the idea that liberty could be founded on rebellion and unbelief.

This conviction deepened as they became alienated from Britain itself, which they believed had grown spiritually weak, morally compromised, and indifferent to the old faith. The Church of England had faltered. The state had tolerated dissent. And Britain, as a consequence, suffered defeat at the hands of God through Napoleon.

"The Upper Canadian Tories believed that England had grown spiritually weak, and that her defeats by Napoleon were a providential rebuke… Ontario, by contrast, remained a fortress of Anglican orthodoxy and moral order."

— Robert Passfield, The Upper Canadian Anglican Tory Mind

In the fire and blood, in the ruined towns and shattered bonds of colonial America, a counter-revolution began to take shape. What emerged was a distilled political type, forged by betrayal, hardened by exile, and defined by its rejection of the revolutionary age. A selection event, like that which shaped French Canada after its severance from liberal, republican France. The moderate, indifferent, and the opportunistic were stripped away, leaving only those most committed to an older vision of order.

"The revolutionaries in France had brought infidelity and anarchy. The revolutionaries in America had sanctified rebellion and turned it into a constitutional principle. England had failed to resist either with vigour. The Loyalists would succeed where the mother country had faltered."

— Robert Passfield, The Upper Canadian Anglican Tory Mind

What remained was not liberal, not tolerant, and not reformist. It was illiberal, anti-democratic, traditionalist. It did not seek to adapt to the age of revolutions. It sought to annihilate it. The Loyalists who would build Ontario witnessed the old world suffer in collapse. They came north as survivors of a civilisational disaster.And they vowed never to let it happen again.

The Idea of Loyality

Many Canadians and Americans alike are extremely ignorant on what Loyalism actually was. Loyalism was not an attachment to the monarchy, or a colonial sentimentality toward Britain. It was a belief system that conceived of government, law, and society as reflections of divine order. The American and French revolutions, were viewed as direct assaults on God's sovereignty and the moral architecture of civilisation. Revolution did not signify progress. It marked the apex of humanity’s fall from grace, the enthronement of will over law, reason over revelation, man over God.

The Loyalists were clear and unanimous: the American rebellion was the product of long-standing religious defection. They declared:

“The American rebellion grew out of the defection of the Puritans from the Church [of England],”

From the outset of their settlement in New England, the Puritans had aimed at political and ecclesiastical independence, submitting to royal authority only reluctantly and sporadically. Massachusetts specifically was viewed as having operated “very much upon the plan of an independent Society,” acting like a sovereign state long before the Revolution — engaging in foreign diplomacy, defying imperial trade laws, and resisting central authority at every turn.

This insubordinate disposition was the fruit of a theological rupture. The Puritans rejected episcopacy, the moral order of the Anglican Church, and the sacramental structure of Christian society. Their religion was disgustingly sectarian, their governance confused and congregational, and their politics demonically republican. From this emerged a spirit of treason. The Loyalists insisted that these colonies were “never attached to the Parent State,” and were restrained only by fear of French aggression, a fear that vanished with the British victory in 1763.

When that threat was removed, and Britain sought to recoup war expenses of defending the colonies against France through taxation, the rebellion of Massachusetts exploded into action. Believing that Puritan Massachusetts deliberately incited the other colonies with exaggerations, lies and criminal agitation, manipulating grievance to spark widespread sedition.

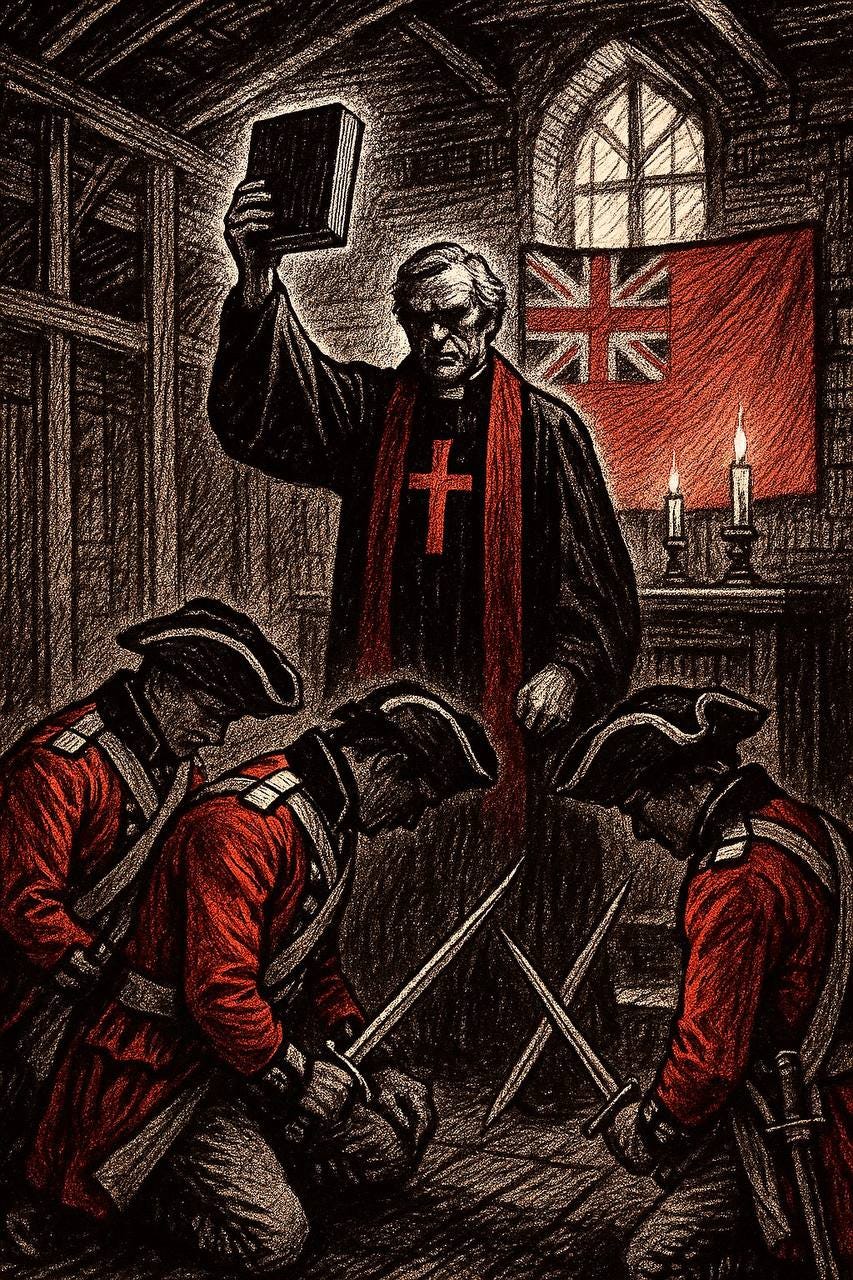

They hated the dissenting clergy the most.

The Loyalists believed that the British government's failure to establish a robust Anglican clergy in the colonies allowed sectarian heretic ministers to dominate the religious and political imagination of the people. These evangelical preachers, especially in New England, were among the American Revolution’s fiercest propagandists. They answered Congress’s call to spread sedition “with the most hearty alacrity,” and even preached “the “Turkish doctrine”, meaning Islam, that “whoever was killed by the King's troops in battle was sure of going to heaven.” The Anglican clergy, were put in chains or silenced when they preached peace.

The Loyalists drew a sharp line between themselves and the Virginians down in Dixie as well. Though Virginia had a nominally established Church, it had succumbed to “secular habits.” Its Anglicanism had become shallow and procedural. By the Revolution, Virginians were “oblivious to the deeper meaning, principles and values of Anglicanism,” and thus equally prone to rebellion.

The Loyalists held that the Revolution began not in Philadelphia but in the pulpits. It was a war born in heresy and matured in debauched anarchy. Only a reestablished Church could forestall such apostasy in the future. This conviction would shape the clerical and constitutional architecture of Ontario from its inception.

"The so-called 'Age of Reason' of the 17th and 18th centuries was an irreligious and irrational age… that viewed government as established only to protect life, liberty, and property without an overriding moral purpose." (Passfield)

Such a view was monstrous to the Loyalist mind. Government was not a social contract, but, in Passfield’s words,

"a sacred trust for upholding the public Good." (Passfield)

The public Good could only be known through revelation, history, and hierarchy.

At the centre of the Loyalist system stood a metaphysical claim: man is fallen. Liberty is not man’s birthright. It is a moral condition, the product of self-restraint, spiritual discipline, and lawful obedience.

"As Christians, they believed in original sin… that man in his natural state was prone to evil… only through faith in Christ and baptism into the Christian Church… could man be justified and enabled to live a life of good works, charity and self-restraint." (Passfield)

Thus, the “freedom” offered by the American revolutionaries was not true freedom, but licence. The Loyalists saw the chaos and death of the French Revolution, the cult of reason, the guillotine, the goddess enthroned, as the logical fruit of a system that denied original sin and elevated man as his own sovereign.

"The French people had rejected God's revealed Will as a standard of conduct for man and government, and turned to the mind of man… schooled by Rousseau to deny the reality of truth and virtue. The French Revolution… inspired religious dissenters, democrats, and infidels to attack the traditional social order and the established Christian churches of Europe." (Passfield)

Against this storm of ideology, the Loyalists upheld the British Constitution and the Magna Carta as a providential order, the visible expression of centuries of tempering and restraint. They rejected the revolutionary claim that government must originate in the will of the people. For them, the people were not sovereign — God was. Authority flowed from above: from God to king, from king to law, and from law to subject. To dismantle it in the name of popular sovereignty was sacrilege.

Theocratic Monarchy

This belief system was reinforced institutionally through the Constitutional Act of 1791, a deliberately counter-revolutionary document intended to “assimilate the Constitution of that Province to that of Great Britain, as nearly as the… situation of the Province will admit.” The Act created an appointive Legislative Council in the likeness of the British Lords, specifically to insulate the colony from “the radical contagion” that had dissolved upper houses in the American colonies.

The Loyalist order was not neutral in religious matters. It rested on the absolute necessity of a state religion, one capable of forming character and restraining passions through the sacraments, the liturgy, and education. Loyalists rejected the American model of religious pluralism as corrosive and immoral. They feared the disestablishment of religion would lead to sectarianism, vice, and chaos.

"The Anglican Tories of Upper Canada… believed in the union of Church and State, in a national system of education based on religion, and the need for the institutions of the state to form the national character of the people on a sound moral and religious basis."

(Passfield, The Upper Canadian Anglican Tory Mind)

The Clergy Reserves were the material foundation of a theopolitical vision, a means of ensuring that faith and governance would never be separated in the new province. The Church of England was upheld “to combat and repress the prevailing disposition of the Colonies to republicanism, and excite in them an esteem for monarchy.”

The young were not to be taught freedom of thought, but right thought. The Bible, the Book of Common Prayer, and British history were the core of the Loyalist schoolroom. The purpose of learning was not self-actualisation, but the inculcation of duty, reverence, and submission to lawful authority. Knowledge was not fragmented into subjective opinion. It was unified by truth, accessible through revelation, tradition, and the teachings of the Church.

"They believed also in civil duties as well as civil rights, public virtue, the concept of the common good, the historic 'rights of Englishmen', and in the balanced British Constitution under the sovereignty of the Crown and the rule of law."

(Passfield, The Upper Canadian Anglican Tory Mind)

Rights were not innovations. They were inheritances. Their defence was not a matter of consent, but of fidelity. They understood revolution as the theological end of Christendom, an anti-Christian apocalypse. The image of the revolution was the image of the tower of Babel rebuilt — the triumph of confusion, pride, and dissolution. Thomas Paine as a corrupter of souls, a man whose writings would destroy the moral fabric of every society that accepted them.

"There was no concept of the sovereignty of God, of the king being God’s vicegerent… Paine rejected prescriptive rights and hereditary rights, and maintained that each generation had the right to act for itself to form its government."

(Passfield, The Upper Canadian Anglican Tory Mind)

This was nihilism. A society without tradition, obligation, or metaphysical anchor. Canada would be the opposite. It would be tradition institutionalised. Obligation incarnate. It would be a world of fathers and sons, pulpits and altars, loyalty and law. Ontarians saw themselves as the final remnant — the preservers of a moral and political order that Britain itself had failed to defend. The holy blades of the Empire. They were not colonial exiles. They were the last true Tories.

Loyalism was a deliberate counter-revolutionary poltical theology, built to withstand the collapse of the world brought by the liberal englightenment. And in Ontario, it did not remain theory. It became government. It became a new people.

Exodus, and the Protestant Rome

The American Revolution did not end with the Treaty of Paris. It continued through the Loyalist exodus. Between 60,000 and 80,000 Loyalists chose not to remain in the republic born of profligate heresy. They had been tested by fire, and chosen by Providence to build a purified society untainted by republicanism.

The first waves of Loyalist migration occurred between 1783 and 1784, with more than 10,000 settling along the north shore of the St. Lawrence River and the Bay of Quinte, eventually expanding into the Niagara Peninsula and beyond. Though the first settlement in what would become Ontario began in 1784 at Kingston. It was no accident that this became the seedbed of Anglo-Canada. Strategically positioned along the military and naval axis of Lake Ontario, and already fortified by the old French Fort Frontenac, where Kingston stands. It became the Urheimat of Ontarians.

Under the leadership of Sir Frederick Haldimand, a Swiss mercenary in British service who had trained in the Prussian army, the Loyalists were brought north in organised waves, escorted by military detachments or naval squadrons along the St. Lawrence River. The initial settlers were largely drawn from the King’s Royal Regiment of New York, Butler’s Rangers, and the Queen’s Rangers, as well as provincial regiments and militia companies that had served faithfully in defence of the Crown.

The province was born in uniform. A vast portion of the new arrivals were either veterans or the families of veterans. The land they settled had been promised in exchange for military service. The Crown granted land as reward for loyalty and obligation to future service. Each officer received land based on rank, with privates and non-commissioned men also granted parcels. Civilians loyal to the Crown received smaller but comparable grants, and children of Loyalists were also entitled to land upon coming of age or marriage. Settlers were registered in special rolls and distinguished from all future settlers by their status as “United Empire Loyalists.” Alongside them came Anglican clergy, and government administrators who received tracts along the Grand River in recognition of their faithfulness and sacrifice.

This was calculated act of geopolitical reconstruction, overseen by men like Haldimand and later John Graves Simcoe, the first Lieutenant-Governor of Ontario. Simcoe envisioned a permanent military-civilian frontier society, one whose very layout would reflect the virtues of defence, discipline, and hierarchy. From the beginning, the settlements were not conceived as frontier freeholds as in New England. They were to be ordered, hierarchical communities governed by law and formed by Church and Crown. Townships were laid out in survey grids with reserved lots for the Crown and clergy. Clergy reserves comprised one-seventh of all granted land, intended to fund and sustain the established Church of England forever.

Simcoe’s government oversaw this process with precision and military logic. Applicants had to prove loyalty, good character, and capacity to improve the land. Town lots were granted based on utility to the economy. Shipwrights were preferred over weavers along navigable waters. Conditions for holding land along these roads were strict: a settler had to reside within a year, build a house of specified dimensions, clear and fence five acres, and open the road along the frontage of the lot. The intention was to populate and shape a moral people, obedient, settled, and structured.

The most ambitious component of early Ontario’s settlement was its road system. Lieutenant Governor Simcoe believed infrastructure would be the spine of the province. Yonge Street was carved out in 1794 from York (Toronto), to Lake Simcoe, intended as a military route for deploying troops to the upper Great Lakes in case of war with the United States. It was followed by Dundas Street, a major route spanning from Lake Ontario westward to the Thames River. To construct these highways, Simcoe formed a militia corps—the Queen’s Rangers—a Loyalist regiment reconstituted for peacetime duties, such as roadbuilding and land clearing. Their work was both civil and symbolic: they carved order into the wilderness, enforced authority on the frontier, and laid the groundwork for Loyalist civic life.

These roads were the were corridors of civilisation. The settlements that sprouted along them were anchored by Anglican parishes, schoolhouses, and magistrates. Simcoe envisioned them as concentric ripples of Canadian order extending from the urban core outward to the lakes and forests.

The landscape of early Ontario was inseparable from martial logic. Local militias were embedded into township life. All able-bodied men were enrolled, drilled, and expected to respond on command. Militia muster rolls served not only a defensive function, but also a civilising one. They were the organs of enforcement. Refusal to serve could mean exclusion from land grants, ostracism, or worse. As one colonial military official put it, “In this province, the musket is the plough.” Military virtue was civil virtue. The Loyalist regime was not a garrison state in name only.

A bastion, what remained was a people forged in order, shaped by sacrifice, and armed in the defence of civilisation. Ontario was a militarized theocratic-monarchist state where every Anglican church stood near a powder magazine, and every town was a redoubt in the war for Order and the Good, against damnable evil and chaos.

By the 1790s, under Simcoe's administration, this military foundation was fused into the provincial structure. The Lieutenant-Governor himself was the Commander-in-Chief, and his Executive Council functioned as a quasi-general staff. Newer roads were laid out to accommodate the movement of regiments. Forts were improved and manned. Naval squadrons were maintained on the Great Lakes to patrol the border with the United States. Inland water routes were linked to a fortified system from Kingston to the western posts. The vision was of an internally mobile, self-reinforcing Christian monarchy buffered by clergy reserves, ordered land tenure, and roads wide enough for cannon transport. And in every aspect of civic life—from land titling to school curricula to Sabbath observance—the assumption was that the spiritual war, the counter- revolution, had not ended. It had simply moved north.

The Great Canadian Holy War

The War of 1812 marked a watershed in the development of Anglo-Canadian identity, particularly in Ontario. Though the war was but one front in the broader conflict between Britain and the United States, for British North America it became a deeply symbolic test of allegiance, a spiritual reckoning that solidified the myth of a Loyalist society rooted in fidelity to crown, order and God. For the Anglican Tory elite, it affirmed what they saw as the colony’s providential role as a bulwark against the septic scourge of republicanism, radical democracy, and American expansionism. Through battle, sacrifice, and collective mobilization, the war became fold in the forge in which a distinctly Anglo-Canadian ethos was forged.

At the heart of this emerging mythology stood Major-General Sir Isaac Brock, whose name became synonymous with both martial courage and sacred sacrifice. As the acting administrator of Upper Canada and commander of British forces, Brock wasted no time in assuming the mantle of offensive war. His stunning capture of Detroit in August 1812, accomplished with a fraction of the opposing force and no real siege artillery, established him as a military genius and a symbol of aggressive Loyalist resolve. Brock's threat to unleash auxilliary Indigenous forces, though more psychological than literal, terrified the American commander, General William Hull, into capitulating. It was a moment of triumph for Anglo-Canadians, confirming that strength of will and imperial solidarity could defeat superior numbers.

But Brock’s legend was secured not through victory alone, but through his death in battle. On October 13, 1812, while leading a counterattack at the Battle of Queenston Heights, Brock was fatally shot while rallying his troops. His final moments were immortalized in both military lore and public devotion. His last words were reportedly "Push on, brave York Volunteers," a phrase that would echo in Anglo-Canadian memory for generations. Queenston Heights was won that day not only through Canadian resilience, the presence of which on the heights helped turn back the American crossing and saved the Niagara frontier from collapse

Anglo-Canadian heroism was not confined to generals. The most enduring civilian participant in the mythos of 1812 was Laura Secord, a Loyalist woman of modest means who became a symbol of imperial vigilance. In June 1813, upon overhearing American officers discussing a surprise attack on British outposts, Secord embarked on a perilous thirty kilometre journey through field and forest to warn the British garrison under Captain James FitzGibbon. Her warning enabled FitzGibbon to prepare his force, which, though vastly outnumbered, ambushed and defeated the Americans at the Battle of Beaver Dams on June 24. FitzGibbon later credited Secord's warning as instrumental. The event entered the national imagination as a parable of civilian sacrifice, Loyalist duty, and the quiet strength of women.

That same summer, another crisis unfolded at the western edge of Ontario. In July 1812, the Americans crossed into Upper Canadian territory and occupied Amherstburg, initiating a series of seesaw engagements around the Detroit frontier. While Brock’s seizure of Detroit had momentarily stabilized the situation, the arrival of fresh American forces reversed Canadian fortunes. In October 1813, General Henry Procter, with dwindling supplies and failing morale, attempted a retreat from Amherstburg. Pursued by General William Henry Harrison, Procter’s rear guard was annihilated at the Battle of the Thames near Moraviantown.

It was on Ontarian soil, however, at the Battle of Crysler’s Farm on November 11, 1813, that the second American prong was definitively broken. General James Wilkinson, moving down the St Lawrence with over eight thousand men, was confronted by a small Canadian force of around nine hundred regulars and militia led by Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Wanton Morrison. Morrison, making clever use of terrain, timing, and field discipline, inflicted a decisive defeat on the Americans, who suffered heavy casualties and retreated across the border. Crysler’s Farm was not just a tactical victory. It was a moral triumph, a clear sign that the Anglo-Canadian border would not be easily breached, and that Canadian forces, when well-led and well-supported by local inhabitants, could withstand even massive invasions.

These battles at Detroit, Queenston Heights, Beaver Dams, the Thames, and Crysler’s Farm formed the heroic foundation of postwar Anglo-Canadian memory. They were cast not as isolated military incidents, but as chapters in a grand narrative of divine preservation and imperial cohesion. Victory was not measured merely by the holding of territory, but by the reaffirmation of values. Obedience, loyalty, faith, and sacrifice became the code of Anglo-Canadian society. In the aftermath of war, these values would be enshrined in political ideology by the Tory elite, especially the Family Compact, who claimed the war as vindication of their vision for Upper Canada, a vision of a hierarchical society grounded in British law, Anglican authority, and paternal rule.

Before the Family Compact could fully institutionalize this memory and its moral order, it was the soldiers, civilians, and local commanders, many of them settlers and immigrants, who turned back the tide and defined the boundaries of British Canada. Their heroism on the front lines and in the forests ensured not just survival, but the sanctification of Upper Canada as a land bought in blood and held by loyalty.

Ontarian Aristocracy

The Family Compact was the informal but entrenched elite of early Ontario: a network of Anglican clergy, Loyalist descendants, military officers, generals, legal professionals, and Crown administrators who dominated the province’s institutions from the 1790s to the 1840s. Their authority rested on a belief that they were guardians of a divinely ordered society rooted in monarchy, faith, and law. As a governing caste, they fused spiritual and political authority, drawing from pre-liberal enlightenment conservative traditions shaped by Hooker, Burke, Blackstone, and Anglican theology. Church and Crown stood in deliberate alliance, tasked with preserving order in the Canadian wilderness.

Though their critics coined “Family Compact” as a term of contempt, suggesting closed ranks and nepotism, the group operated more as a cultural priesthood. Membership was bound by shared convictions. All saw Upper Canada as a providential order, and their role within it as a defence against the revolutionary forces that had overturned the old world. All upheld a vision of Upper Canada as a providential society, governed by divine law and stewarded by a moral elite. Their ideological mission was to serve as a bulwark against the revolutionary spirit that had shattered the Old World. At the centre of this elite stood John Strachan, priest, educator, and political theologian, whose spiritual authority was inseparable from his civil influence. He viewed kings as divinely appointed fathers and clergy as responsible for the moral health of the nation. Strachan and his allies did not believe government was a contract among equals, but an expression of divine will. Order, not consent, was the origin of authority.

“Government under which society exists is the ordinance and institution of God, and not of the people.”

— Passfield, The Upper Canadian Anglican Tory Mind

The Crown granted one-seventh of all surveyed land in Upper Canada to the Church as Clergy Reserves. These lands were administered by the Clergy Corporation, established in 1819, and provided income for ministers, construction of churches, and rural missionary work. This ensured that religious authority was geographically rooted in both frontier and town. In tandem, the Compact built an elite education system to reproduce its values across generations. It founded and controlled King’s College (later the University of Toronto), Upper Canada College, and the grammar school system. The goal was to train a future ruling class in Anglican doctrine and monarchist virtue. Students were taught the duties of station, and obedience to God and Crown.

“To inculcate reverence, duty, and submission to authority.”

— Mills, The Idea of Loyalty

The Compact’s institutional reach extended across the colony. Its members held the highest posts in the Executive and Legislative Councils, directed policy through the lieutenant governor’s office, and staffed the judiciary with loyal magistrates and judges. John Beverley Robinson and Christopher Hagerman oversaw legal affairs; William Allan chaired the Bank of Upper Canada, which controlled credit and shaped infrastructure development; Strachan himself guided religious and educational affairs with near-total authority.

The Bank of Upper Canada, chartered in 1821, served as the Compact’s financial engine. It issued currency, controlled credit, and directed the funding of canals, roads, and government salaries. In doing so, it ensured that economic development remained in loyalist, Anglican hands. Public funds and access to land were allocated not by need or merit, but by ideological reliability.

Appointments to local offices, surveyors, registrars, schoolmasters, and militia officers, were similarly dispensed through patronage. The result was a colony ruled by a stable, interwoven caste. The Compact curated the entire social order.

Reformers were cast as enemies of Church and Crown, their demands for elected government and religious pluralism condemned as revolutionary subversion. Strachan in particular warned that tolerating heterodoxy would lead to disorder and impiety.

“[Strachan] warned that their efforts would open the gates to ‘the sectarian mob’ and dissolve the unity of throne and altar.”

— McKim, Upper Canadian Thermidor

Even in crisis, the Family Compact held firm. During the 1837 Rebellion, its members organised militias, led loyalist suppression efforts, coordinated intelligence, and directed reprisals. Their authority was not abstract; it was exercised through direct, coercive power. At its core, the Compact was defined by moral certainty. It upheld hierarchy as sacred, and saw liberty not as individual autonomy but as obedience to divine order through lawful institutions. The language of equality and democracy was regarded as subversive, even blasphemous.

The “Reformers”

Yet by the 1830s, the foundations of Compact rule were weakening. Immigration from the United States, along with the rise of Methodists and Presbyterians, diluted its Anglican base. Reformers increasingly challenged its control over land, education, and governance. Though the Compact maintained dominance through patronage and clerical networks, it faced growing public resistance.

The Reformers were liberal British constitutionalists, who sought to restore what they believed to be the proper balance of the British Constitution. Figures such as William Warren Baldwin and his son Robert Baldwin led the intellectual charge. In 1828, Baldwin introduced the concept of responsible government: that the Executive Council should hold the confidence of the elected Assembly and be answerable to it, not to the Governor alone. This principle gained traction among reform-minded elites and rural dissenters alike.

As Passfield notes, Baldwin and his allies envisioned a system where “the Crown would retain control over Imperial trade and defence, but would concede authority over the provincial revenues, provincial government patronage, and local affairs to the provincial government through instructing the Lt. Governor to accept the advice of his Executive Council on local matters.”

By the early 1830s, disparate reform factions coalesced under this banner. They rejected the non-partisan Tory vision of an executive isolated from the people and instead insisted on democratic accountability. David Mills explains that when Lord Durham issued his 1839 Report on the Affairs of British North America, condemning the Compact and endorsing responsible government, it was greeted with jubilation by the Reformers. Francis Hincks exclaimed, “No document has ever been promulgated in British North America that has given such general satisfaction as this.”

The 1837–1838 rebellions, though swiftly crushed, Reformers had long accused the Compact of obstructing representative government and monopolising colonial power. The uprisings gave imperial authorities reason to re-evaluate the system. Durham’s Report identified the core problem as the absence of responsible government, a system in which the executive was answerable not to the governor, but to the elected assembly. Durham recommended aligning colonial institutions with the will of the people to prevent further unrest.

Tories were appalled. John Beverley Robinson wrote that Durham’s report “absolutely made me ill.” The Church newspaper countered that Canada could not safely implement democratic government until it possessed “a hereditary peerage, a wealthy country gentry, and the full operation of the principle of an established religion.”

A land owning elite.

The turning point came with the 1841 union of Upper and Lower Canada into the Province of Canada. Intended to stabilise administration and reduce ethnic conflict, the union also laid the groundwork for reform. In 1848, the British government accepted the principle of responsible government. From that point forward, the executive council had to command the confidence of the assembly, not merely the approval of the governor or his advisors.

This change rendered the Compact’s apparatus obsolete. Political authority now flowed through elected parties, not through clerical patronage. Reformers like Robert Baldwin, long excluded from power, were invited to form governments. The Compact’s grip on land, education, the judiciary, and finance was steadily dismantled. Anglican privilege gave way to religious pluralism.

The Compact was not toppled by revolution, but by structural transformation. It had been outnumbered, outgrown, and replaced by a more inclusive and representative system. By the 1850s, it existed only as a memory — the last vestige of a hierarchical vision swept aside by parliamentary democracy.

Still, its legacy endured. The Reformers, Methodists, Presbytarians, the Irish, then the Scots, and a final massive wave of English didn’t further British the country, they were assimilated to Loyalist, Anglo-Canadian culture, and only mildly tempered it.

A culture that was unique from the moment those colonists split from the liberal revolutionary Patriots. The land it surveyed, the schools it founded, and the institutional culture it shaped left a lasting mark on Ontario.

Ethnogenesis

The Anglo-Canadians of Ontario were not forged in a single moment but over generations of convergence between Loyalists, and later waves of English, Irish, and Scottish settlers. These were subjects of a shared imperial civilisation. Beginning in 1763, they laid the cultural foundations of what would become Ontario. The population of Upper Canada rose from 14,000 in 1791 to over 95,000 by 1814, driven by high birth rates and steady migration from the American colonies and the British Isles. Each group carried regional traditions that merged over time into a distinct Anglo-Canadian identity.

Each group was propelled by historical upheavals:

The Irish arrived in large numbers fleeing the Great Famine (1845–1852) and political turmoil, settling both in rural communities and urban trades.

The Scots were driven by the Highland Clearances and land enclosures in the 18th and 19th centuries, forming tight-knit Presbyterian enclaves in Ontario’s countryside.

The English migrated before, during and after the Industrial Revolution, seeking land and relief from the urban dislocation of industrialising Britain. They often dominated administrative, commercial, and clerical roles.

These waves of settlers did not remain distinct. Through shared institutions — the Anglican Church, parliamentary government, common law, and civic associations — they fused into a common people: Anglo-Canadians. They were not defined by race alone, but by ethnos, a shared moral order, cultural ancestry, and institutional loyalty. According to the 2021 Canadian census, Ontario’s population includes:

Ontario's total population (2021): ~14.2 million

Estimated White population in Ontario: ~9.8 to 10.5 million

British Isles ancestry in Ontario:

English: ~3.6 million

Irish: ~3.4 million

Scottish: ~2.6 million

Overlap acknowledged but not fully disaggregated

Total number identifying with one or more British ancestries: ~5 to 6 million

Ontario’s total population in 2021 was about 14.2 million. The overall White population was roughly 9.8 to 10.5 million, depending on how it's measured. This means that British Canadians alone account for most of Ontario’s white population. Together, these groups represent the majority in Ontario and more than half of Canada’s total Anglo-Canadian population, which exceeds 10 million nationwide. In Ontario alone, over 5 million Ontarians identify with one or more British Isles ancestries. This makes Anglo-Canadians the overwhelming majority of Ontario’s white population. Though Ontario has become more ethnically diverse, most white Ontarians continue to trace their lineage to the British Isles.

The Names That Built Ontario

The most common surnames in Ontario today bear witness to this British Isles convergence. According to Statistics Canada and genealogical studies, the top 30 surnames in Ontario include:

Smith

Brown

Taylor

Wilson

Johnson

Campbell

Anderson

Thompson

MacDonald

Moore

Martin

Murphy

White

Walker

Young

Clark

Hall

Wright

Robinson

King

Scott

Green

Lewis

Hughes

Ross

Reid

Hamilton

Mitchell

Graham

Fraser

These names are overwhelmingly Anglo — English, Irish, or Scottish — and mirror the exact trajectory described by Duchesne. They are the living remnants of a settler population that built Ontario’s farms, courts, churches, and schools.

Canada only ever made sense as a conservative project — a fortress of order on the edge of a revolutionary continent. And it still does. We were the first to reject the liberalism. We may be the last left standing when it burns itself down.

Sources

Passfield, Robert W. The Upper Canadian Anglican Tory Mind: A Cultural Fragment. Rock’s Mills Press, 2018.

Mills, David. The Idea of Loyalty in Upper Canada, 1784–1850. McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1988.

Grant, George. Lament for a Nation: The Defeat of Canadian Nationalism. McClelland & Stewart, 1965.

Duchesne, Ricardo. Canada in Decay: Mass Immigration, Diversity, and the Ethnocide of Euro-Canadians. 2nd ed., Black House Publishing, 2018.

Upper Canadian Thermidor. Manuscript.

Statistics Canada. 2021 Census of Population. Government of Canada. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021

Wikipedia contributors. “Family Compact.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Family_Compact

Wikipedia contributors. “Loyalist (American Revolution).” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Loyalist_(American_Revolution)

Wikipedia contributors. “Ontario.” Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ontario

The Anglophones, Francophones & Gallophones forged Canada from nothing. It was their spirit and their mettle that forged something from nothing.

I loved this essay, and it amuses me to no end that having done some testing of my DNA, there's only really Scotch and Franc DNA in me so none of my ancestors were involved in 1812 save for one Scot who came over to apparently slaughter Americans, in exchange for a farm (apparently he got one, and then learnt French, married into Quebec).

Ours is the Loyalist nation, and much of the traditional Scottish, Anglo, and Francish culture I love and was raised in that forms the bedrock and spine of Canada and Europe is what I've poured into my novels.

I'll need to have a look at your sources to better entrench myself philosophically in my racines and in Canada though.

Good article.

Since you mentioned it I'd like to take the opportunity to brag that one of my Loyalist ancestors was a member of Butler's Rangers.